After talking so much about the major scale on these pages, a minor scales primer seems to be in order. In some ways the minor scale should be easier to understand once you know the major scale. The minor scale is derived from the major scale.

But the minor scale presents a complication. Actually three forms, or variations, of the minor scale exist. Let’s take a look.

What is the minor scale?

In music the minor scale is a series of seven notes from an octave. Like the major scale, the minor scale starts with the root note of the key. For instance, in the key of C minor, C is the root note and the first note of the scale. The minor scale uses the same notes as the major scale with three modifications. The third, sixth, and seventh notes of the major scale are flattened to create the minor scale. So the C minor scale consists of the notes C, D, Eb, F, G, Ab, Bb. Every major scale has a minor counterpart that follows the same I, II, bIII, IV, V, bVI, bVII formula.

Don’t know the major scale? Start with

Why do people sometimes say there are three minor scales?

The minor scales have an interesting history. The main scale–the natural minor–evolved out of the ancient system of modes in which the minor key was (and still is) the Aeolian mode. We’ll have to talk about modes in another article. But for now, just realize that the Aeolian mode is just another name for the major key’s relative minor. It’s also called the natural minor.

Need to understand the term relative minor?

I already discussed the minor scale in my article Learn the minor scale. There I concentrate on the natural minor scale. You should take a few moments to read that article if you don’t already understand that scale, though I’ll review it below.

But I also mention in that article that two other minor scale forms exist. In this minor scales primer, let’s take a closer look at those two scales.

A quick review of the natural minor scale

Play the natural minor scale on your guitar. For instance, let’s play it in A. Remember that the formula for the natural minor scale is:

W-H-W-W-H-W-W

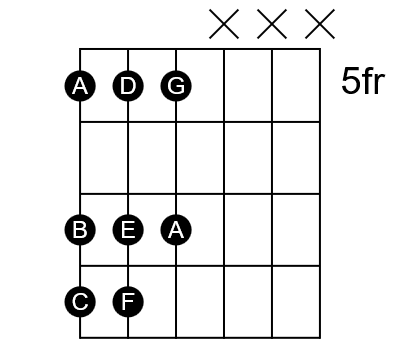

You can play the entire scale across four frets with two or three notes per string. Start with your pointer on fret 5 of the Low E string for the root note, A. Then a whole step to fret 7 of the same string with your ring finger for B. Next a half step and fret 8 with your pinky for a C. Remember that A major uses C# for the third scale degree, but the natural minor has a flatted 3rd, so that gives us C instead.

Next move to the A string and play the same three frets and the same fingering. Fret five gives the note D. At fret 7 you have E. And finally, at fret 8 you have F. The F would normally be F# in A major, so that’s your flatted 6th scale degree.

Move to the D string and play the G note at fret 5. That’s the flatted 7th note since the A major scale uses G#. And finally one last whole step back to the A at fret 7 of the D string with your ring finger.

You’ve just played the natural minor scale. While it sounds nice enough, there’s something just a little…weak…about it. It lacks a half step from the 7th back to the root. In other words, the natural minor scale doesn’t have a strong leading tone to take you back to the root.

Play the scale again and listen for the lacking leading tone.

The harmonic minor scale

That lack of leading tone from the 7th back to the root makes melodies a little less interesting than they could be. It’s kind of bland.

I’ve talked in a couple of different articles about tension and release. In the major scale, that leading tone–that half step between the 7th and the root–gives you a strong device with which to lead your listener back to the root. That leading tone sets up a tension that makes melodies interesting. And the tension is released when you move from the 7th to the root.

Sometime around the 1600s composers developed a longing for that tension-and-release device in their minor-key songs. It was about that time they started to modify the natural minor key.

The first modification involved substituting the natural 7th (the same note as the major key uses) for the flatted 7th. This became known as the harmonic minor scale.

The harmonic minor scale follows this formula:

W-H-W-W-H-W1/2-H

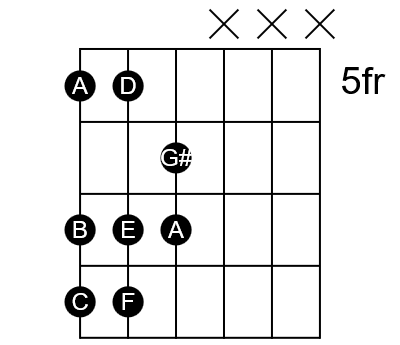

To play the harmonic minor scale on your guitar, use the same fingering as outlined above for the natural minor. Except, instead of the G note at fret 5 of the D string, use your ring finger to play G# at fret 6.

Notice the difference between this and the natural minor scale. The harmonic minor has a much stronger resolution back to the root. It might even feel more comfortable to you since it sounds more like the major scale now.

The melodic minor scale

While the harmonic minor scale solved one problem for composers, it created another. Now they had the strong tension and release they wanted between the 7th and root.

But look at the scale formula again. Notice that there now exists a whole step and a half between the 6th and 7th degrees. That’s a big leap for any scale, and it leaves the harmonic minor scale a bit awkward in a way.

Composers didn’t like this big leap, so they fixed it by moving the 6th degree up one fret along with the 7th. The melodic minor scale formula then became:

W-H-W-W-W-W-H

Notice that this is almost identical to the major scale formula. Just the 2nd and 3rd intervals are swapped.

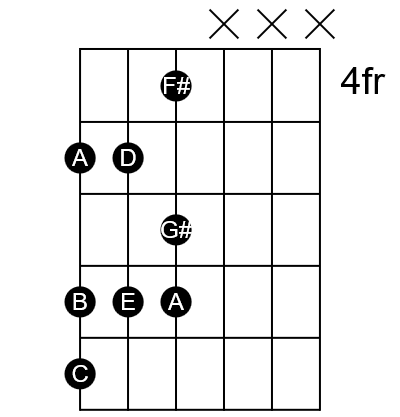

To play this scale, start with the same three notes and fingering on the Low E string. Play just the first two notes on the A string. That’s the D at fret 5 and E at fret 7.

Reach back with your pointer to play the F# note at fret 4 of the D string. Then play the G# with your ring finger at fret 6. Finish with a half step to fret 7 with your pinky back to the root note.

Now you have comfortable intervals between all the scale degrees. And you have a strong lead-in from the 6th to the 7th, along with the tension and release of the leading tone (the 7th) back to the root.

You only need the melodic minor scale on the way up

It’s interesting to note that on the way back down the scale, you don’t have the same problems of leading tones and discomfort caused by the flatted notes. These things just don’t strike your ear as not right.

So, composers developed the habit of using the melodic minor scale on the way up from low notes to high notes. But they switched back to the natural minor scale on the way back down.

I don’t see any reason you couldn’t do whatever you wanted to. But clearly composers who are far more trained than I have agreed that one scale up and the other down makes good sense.

What does all this mean for you as a guitarist?

For many of us guitarists, these different minor scale forms aren’t going to change much about the way we play. Especially if we’re simply following chord charts, we don’t really need a deep understanding of this. We’ll play chords from one or the other of these forms and maybe not even know which. That’s OK.

But for those of us who want to play solos or for those who want to compose original pieces on guitar, this might be very important understanding to have.

If a song’s chord progression comes out of the harmonic minor scale and you use the flat 7th note from the natural minor scale, you might not like the result. But then, you might, so try it!

As a songwriter or composer, you can open up new melodic possibilities with a simple switch between one of these forms to another. Experiment and see what you can come up with.

One scale, three forms

There’s one last point to make here. Although we sometimes refer to these as three distinct scales, there really exists just one minor scale. That’s the natural minor scale.

The harmonic and melodic minor scales are really just variations of the main natural minor scale. In written music, all three have the same key signature. The two alternate forms are indicated at the individual note level.

So, go ahead and call each of them a scale. But if you really want to impress your music theory nerd friends, insist that they call them forms of the natural minor scale!

Conclusion

Did you anticipate the turns that a minor scales primer could take? The minor scales actually consist of three forms of a single minor scale. The natural minor scale is another name for the Aeolian mode from ancient times.

As music progressed, composers became unsatisfied with the lack of a leading tone in the natural minor scale. Thus they “unflatted” the 7th scale degree to create a strong leading tone. This became the harmonic minor scale.

Having solved one problem, another was created with an extra large interval between degrees 6 and 7. So the 6th degree was unflatted and thus we have the melodic minor form.

Some guitarists won’t really need to worry much about these different forms. But lead guitarists, soloists, songwriters, and composers can all make great use of this knowledge.