Playing over the chord changes can bring a new dimension to your guitar solos and lead lines. Sometimes you hear people call this chord chasing, playing the changes, soloing over chords, and any number of other names. But whatever name it goes by, it’s an interesting concept that can really change the sound and sophistication level of your improvisations and solos.

Soloing with the pentatonic scales

Just as when we talk about soloing in general, when solo over the chord changes, we can lean heavily on the pentatonic scales. The pentatonic scales provide a comfortable framework for solos, lead lines, and improvisations, so they’re great not only for playing, but also for this discussion.

Need to learn more about the pentatonic scales?

In order to effectively play the changes, you really need a firm grasp on the pentatonic scales. This discussion will make little sense without that, so refer to the articles linked above if you need to study up.

Sticking with one scale despite the chord changes

If you’re relatively new at soloing, then it’s likely that when you play your solos you stick to one scale. No matter what the chord changes do, you probably play the same scale over those changes. In other words, you’re not playing the chord changes.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with this approach to soloing. Everyone does it. Even very accomplished players take this approach to soloing at least some of the time.

The crucial key to soloing with this technique involves understanding when to land on which notes in the scale.

For instance, if you’re soloing in the key of A minor, you might use the A minor pentatonic scale throughout the entire solo. When the chord progression reaches A minor, you play the A minor pentatonic. When the progression changes to a D minor chord, you stay on the A minor pentatonic.

It’s all a perfectly legitimate approach. But some notes of the scale simply sound better when the underlying chord is an A minor. Other notes in the same scale work more effectively over the D minor.

And here we’re really talking about “landing notes”. That means those notes that you come to rest on during your solos. Even if a note exists in the scale you’re using, it might not sound great as the landing note depending upon the underlying chord in the progression.

The beauty of the pentatonic scale lies in the fact that all of the notes sound at least OK regardless of the underlying chord. But some definitely sound better with some chords than others. You’ll experiment and as time goes by, you’ll begin to develop a real feel for which notes of the scale you like to land on over specific chords.

Again, tons of solos use this one-scale method.

What does playing the chord changes mean?

In the context of a musical solo–such as a guitar solo–“playing the chord changes” indicates that the soloist changes the notes or scale used in the solo according to which chord is present in the underlying chord progression. In this way the solo echoes or implies the chord progression so that even if another instrument weren’t playing that progression, the listener would get a sense of it simply by the notes used in the solo.

This can be a very interesting and sophisticated approach to soloing. But it can also be more difficult since it requires the soloist to have a perfect understanding of the chord progression he’s playing over.

While sticking to one scale or set of notes might let the player “get lost” in the zone, chord chasing requires concentration and attention. In reality, this is probably a distinction without a difference because a good player always stays in touch with the underlying music. And likewise, playing the changes doesn’t have to pull the accomplished player out of “the zone”.

Still, when you’re learning this technique, you might indeed feel like you’re paying more attention to the technique than the music you’re creating.

But playing the changes is both fun and powerful, so let’s take a closer look at a couple of approaches to doing it.

Playing through the chord changes in the key of A major

Sticking to one scale through an entire solo generally works better when you’re using the minor pentatonic scale. Whether you’re using it in a minor-key song or major-key song, it works pretty well to stick to the minor pentatonic scale of the song’s key throughout the entire solo.

For major-key songs however, this approach doesn’t always work so well. Sometimes it just doesn’t sound right. So you might find a chord-chasing approach to be the better option for major keys.

So let’s take a look at an example of working in a major key. Specifically, we’ll work in A major for this discussion.

Let’s say we’re playing a song that uses a four-chord progression. The root chord is A major. The progression also uses the IV, V, and VI chords of the scale. In the key of A major those chords are D, E, and F#m respectively.

Using one box throughout the chord changes

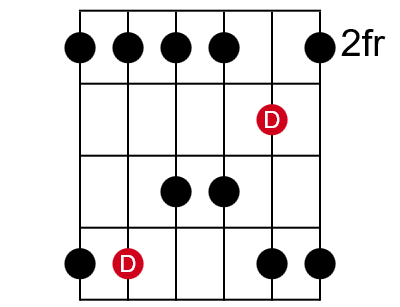

To start out as simply as possible, we’ll stick to one shape of the pentatonic scales at first. This will help you really understand what’s going on. Specifically, we’ll use Box 5 of the major pentatonic scale. Remember that Box 1 of the minor pentatonic scale uses the exact same shape. If you don’t understand this, then you really need to read the articles I linked above!

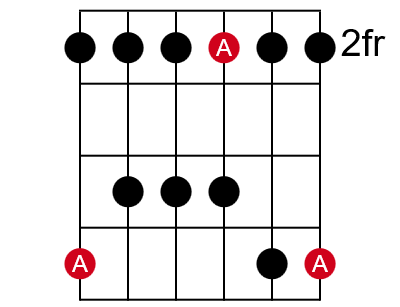

Playing over the A major

In the key of A major, the solo section’s chord progression most likely starts on the A chord. So you’ll use the A major pentatonic over this chord. In order to use Box 5 of the A major pentatonic scale, you’ll play the shape at fret 2.

While the chord progression remains on the A chord, you should start by targeting the root note—the A—as your landing spot. This note works well for you to end your riffs and phrases on.

It’s not a hard and fast rule. After all, this is music, and creativity should win out over rules every time. But it’s a good place for you to start while you’re learning. And frankly, even when you’re a much more sophisticated soloist, you’ll still often come back to landing on the root note of the chord during your solos. It’s just a natural and comfortable place to end phrases and call home. That’s why it’s called the root note, after all.

So long as the chord progression stays on A major, you can pull riffs out of this box.

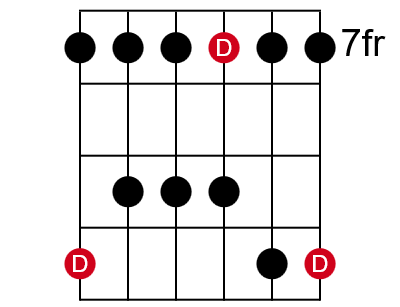

Playing over the D major

After a few bars of A major, the progression moves to the IV chord, a D major. Since you’re following the chord changes in your solo, you’ll need to switch to a D pentatonic. But which should you use: major or minor?

Let the chord guide you. If the chord progression changes to a major chord, you most likely want to use a major pentatonic to play over it. Go ahead and experiment with the minor pentatonic, but most likely you’ll find that the major fits better.

So, for our example, we’ll switch to a D major pentatonic scale for the D major chord.

To find Box 5 of the D major pentatonic scale, you need to jump up to fret 7. Since you’re using the same pentatonic box shape you used over the A chord, you can use literally the same riffs and licks you use over the A chord here over the D chord.

Sometimes, this is actually a really cool approach. When you repeat licks over a different chord, you build in a certain continuity. This can help your listeners feel comfortable. Comfort and familiarity help your listeners connect with your music, and they might not even know why.

But naturally, if you use exactly the same riffs over all chord changes it could get boring. So go ahead an experiment with the same riff. But use your discretion and know when enough of a good thing is enough.

Still, while you’re learning, you can get a lot of mileage out of one simple riff repeated in different positions just to see how the technique works.

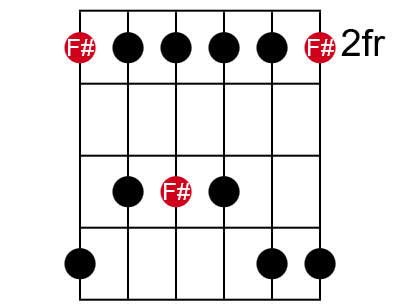

Playing over the F#m

Next the chord progression moves to the VI chord. In the key of A major, that means we move to an F# minor chord.

Again, let the chord dictate whether you play a major or minor pentatonic over it. Since the song moves to F# minor, you’ll want to play F# minor pentatonic over that chord. So we’ll switch to Box 1 of the minor pentatonic for this chord.

Conveniently, F#m is the relative minor of A major. That means that box 1 of the major key’s relative minor uses the exact same notes as Box 5 of the root note’s major pentatonic. In other words, A major pentatonic Box 5 and F#m pentatonic Box 1 are identical.

Need help with the concept of relative minor?

But remember that the key to doing this involves the root note. As we saw above, the root note of the A major scale is A and the chart shows where those root notes sit.

The root note for F#m pentatonic is, of course, F#. So make sure that even though you’re playing the same shape in both cases, you target the F# notes as your landing notes when the chord progression plays F#m.

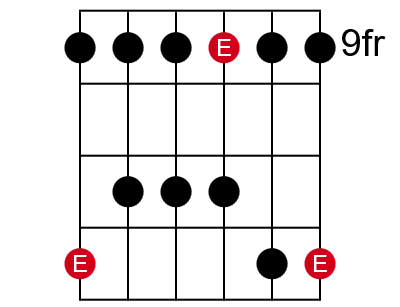

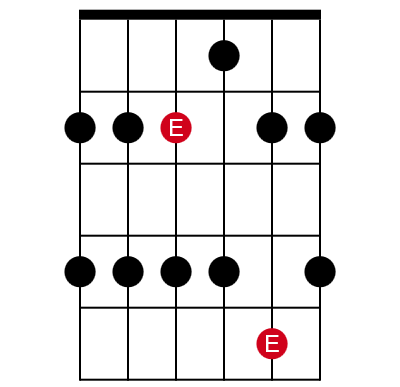

Playing over the E major

Finally, the chord progression moves to the V chord. That’s E in the key of A major. Since it’s another major chord, we need to move back to the major pentatonic.

To play box 5 of the E major pentatonic, move to Fret 9.

Just as before, you can use some of the same licks here. That’s not a bad place to start as you’re learning. But remember to spice things up a bit so your playing doesn’t get boring. Once you’re comfortable switching between these different positions, try mixing some new licks into your playing.

Using different boxes to stay in one area

Now that you’ve got the feel for playing a different pentatonic to match the chord changes, let’s get yet a bit more sophisticated. You may well feel that this method seems awkward. Especially when you jump from the second fret to play over the A chord all the way up to the ninth fret to play over the E.

Maybe you thought there must be a better way. And in fact, if you did, you’re right. Well, maybe it’s not right to call it a better way. It’s another way. Sometimes what you’ve just learned to do may suit you just fine. But other times it can feel clumsy.

To avoid this clumsiness, we can use a couple pieces of knowledge to find that other way.

Finding all the notes you need wherever you are

In my article The notes on the guitar fretboard found everywhere I mention the fact that every note of the chromatic scales exists across all six strings and within any four frets. This fascinating fact of the guitar can help us here. Especially when you combine it with your knowledge that each pentatonic scale—whether major or minor—has five different box shapes. That means that you can play the same scale at five different locations within the first 12 frets.

When you combine these two nuggets of golden guitar knowledge, you might have already come to the realization that you can play over all of the chords in your progression without leaving one general area of the fretboard. Let’s see how it works with the four chords we’ve been working with in the key of A.

Finding the scale shapes you need

In our first example we found that you can use exactly the same box shape over two of the chords in our progression. The A and the F#m chords both use the most common box shape. It’s Box 5 for the major chord and Box 1 for the minor, but as you saw, it’s exactly the same shape for both chords. Only the scale degrees of the notes in the box change according to the chord you’re playing over.

Since we have two chords that use that comfortable shape, let’s base our entire solo around the frets nearby it. That box anchors on fret 2, so we just need to find boxes for the D and E chords that center on (or near) that area. Luckily, it’s quite easy to do.

Find a shape for the D major pentatonic

You first need to find a shape for the D major pentatonic scale that works in the area of frets 2, 3, 4, and 5 (the same as the boxes for the A and F#m scales).

Use your knowledge of the D major scale to find the notes of the scale on the Low E string. The notes of the D major scale are:

D, E, F#, G, A, B, C#

That F# sits at fret 2 of the Low E string, so that indicates that we might indeed find a D major pentatonic box shape there. And, in fact, Box 3 of the D major pentatonic scale starts with your index finger on the F# at fret 2. That’s exactly where the box for the A and F#m starts, so you don’t even have to move your hand position.

Need help figuring out the notes of the D major scale?

Find a shape for the E major pentatonic

In the same way, we just need to find a box that works for the E major pentatonic scale. The notes of the E major scale are:

E, F#, G#, A, B, C#, D#

There’s that F# again! So there must be a shape for the E major pentatonic close by the second fret. Of course, there sure is. Box 2 of E major pentatonic starts on that F# note. Again, you’re already there and you never have to move your hand position.

I don’t know about you, but when I learned this it was a real eye-opening experience. Essentially everything you need to solo over any chord changes exists right within the same four or five frets on the guitar. No matter what key. No matter where you are!

If you didn’t think it was important to know your five pentatonic box shapes before, hopefully you can see the benefits now.

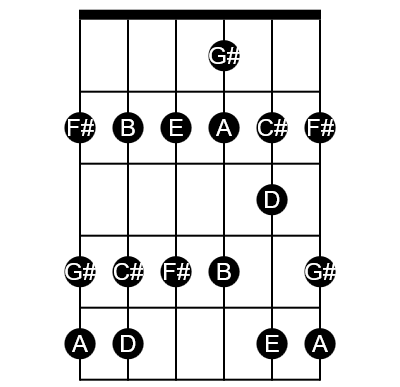

What scale are you really using over the chord changes?

All of this leads to another pretty interesting discovery. What happens when we stack all four (well three really) of these boxes on top of one another? This figure shows all of the notes that are played in at least one of the boxes.

If you know the notes of the A major scale, you soon discover that the notes of each of these pentatonic shapes fall within the A major scale. Specifically, A major consists of:

A, B, C#, D, E, F#, G#

Look at the figure again and notice that those notes–and no others–are all represented. This makes perfect sense because each of the four chords belongs to the key of A major. Since the chords are all in the key, they contain only the notes of the key.

So, this tells us that all along you’ve really just been using the A major scale to solo over the chord changes. But the beautiful thing is that you don’t have to think in the more complicated A major form. The pentatonic box shapes make it easy to know which notes to target over which chords. And that makes playing the chord changes much easier than if you think in terms of the A major scale.

Think ahead to the chord changes

As you practice this technique, you might soon start to develop the feeling that your transitions still don’t feel all that smooth between the various box shapes. And if you think in terms of abruptly switching from one shape to the next at the exact moment of the chord changes, that feeling will be justified.

Jumping between shapes in an abrupt manner like that can indeed seem a bit jarring. Especially if you do it on every chord change. It feels “boxy” for the lack of a better term. So how do you fix that problem?

The solution involves thinking ahead a little bit. If you’re wailing away over the A chord, but you know that the change to the D is coming up soon, think about how you can seamlessly transition from the A pentatonic shape to the D shape.

The two shapes share some common notes, so one approach might be to make sure you’re playing one of those common notes at the moment of the chord change. Another approach might be to “jump” the change a little bit. This means to hit a note that’s in the D major pentatonic box while the chord progression remains on A. Do this maybe on the 4 or 4-and beat of the last measure of A.

It might feel sort of uncomfortable at first. After all, technically you’re playing a “wrong” note. But the dissonance that wrong note brings can be cool if it resolves quickly enough. Will it sound great in your solo? I don’t know. You just have to try some things! Experiment and see what you come up with that you like and find interesting.

Break the rules you’ve learned and see how it works. If it sounds horrible, don’t do it again. If it sounds great, well then you’re on to something! Just keep thinking ahead and try different things to smooth out the transitions between box shapes.

This works no matter what key or what chord changes

Hopefully you’ve seen here just how cool chasing chord changes can be. It’s really quite a jump in sophistication in lead playing. And this technique works no matter what chords and no matter what key. Just remember to match major and minor pentatonic scales to the underlying chord.

Things do get a little more complicated when the chord progression includes out-of-key chords or borrowed chords. For instance, if our little song switched to a bridge section which includes a C chord, we have an out-of-key chord. The chord C is not in the key of A major.

That certainly doesn’t mean it can’t be used. This sort of thing happens all the time in music. You just have to be ready for it. But with the technique you’ve learned here, you can easily adjust. Just play a C major pentatonic scale over that C chord and carry on. You’ll sound great.

In fact, this technique of playing the chord changes gives you a critical tool for dealing with any out-of-key chord. If you’re thinking in terms of the A major scale, you’ll be thrown for a loop when that C chord comes along because suddenly you need notes that are not in the scale you’re concentrating on. If you use this pentatonic approach, you’ll make the change without skipping a beat.

Summary

Soloing with pentatonic scales is an incredibly powerful technique. It’s easy to get started as a beginner, but those same scales will take you far into advanced territory too.

You can use just one pentatonic scale to solo through an entire chord progression. A more sophisticated approach to soloing involves changing pentatonic scales along with the chord changes of the song. Just play the major or minor pentatonic scale that matches the underlying chord.

You can move one pentatonic box shape up and down the neck to play through the changes, but this can feel and sound a bit awkward. To play more smoothly, you can use different pentatonic shapes to play within one area of the fretboard.

When you do this, you’re really just using the major or minor scale for your solo. But thinking in terms of pentatonic shapes makes it far easier to target the right notes for the chord you’re playing over.

Give this technique of playing over the chord changes a try and see how it opens up new ideas in your playing.

Really great article. I learned a lot, thank you!

I’m glad it helped, Gary. I hope you’re making great progress on your playing!

This is what I was looking for a long long time. I always figured out songs by ear one note at a time. Now I am 70 years old and am pumped up to try to do this. I just don’t know how to thank you. I wish I would have know this 50 years ago. LOl. Thankyou so much excellent explanation.

Thanks, Maynard. It’s so gratifying to hear that you found inspiration in this article. I’m no youngster either, but as long as we keep playing and learning, we are still growing. Guitar is a life-long quest, so keep it going!