Your guitar heroes likely all use major triads. Have you ever marveled as you watch a monster guitarist fly up and down the neck and wondered how they know what they’re doing? Well, many techniques enable a player to travel the neck at will. Major triads hold a rightful place as one of the most powerful techniques around. And the good news? Major triads are easy to learn, easy to play, and ready for you to start using even if you’re a relative beginner.

What are major triads?

Major triads are the most basic form of a major chord in music. As the name triad suggests, they contain strictly three notes. These notes are the first, third, and fifth notes that exist within one octave of the major scale regardless of the scale’s key. Three possible combinations of these three notes exist. The first, called the root position, has the note order (from lowest to highest) as the 1st, 3rd, and 5th. The next combination, called the first inversion, orders the notes 3rd, 5th, and 1st. And the last combination, the second inversion, has the note order 5th, 3rd, and 1st. These are all still major triads.

Why are major triads important?

These major triads play a very important role in your playing. You can use them in many different situations and for very different purposes.

You can use them for rhythm playing

As a rhythm-guitar tool, they enable you to play in different locations on the neck other than the open positions. This helps you add variety and interesting sounds to your playing.

Particularly when you’re playing along with another guitarists, you can use major triads to ensure that the two of you don’t just play identical chord shapes. This adds different dimensions to the overall sound.

You can use them for playing leads

Lead guitarist can also use major triads as the basis for lead lines. This enables you to break out of the pentatonic box patterns that we as lead guitarists can tend to overuse.

Want to know all about the pentatonic scale boxes?

You can also use major triads to blur the lines between lead and rhythm playing. For instance, was George Harrison playing lead guitar or a second rhythm guitar part when he played triads in And I love her?

You can also use major triads in chord stabs to accent certain beats of a measure. Again, one could argue over whether this is a lead or rhythm technique, but it really doesn’t matter.

All of this versatility shows just how useful these simple triads can be in a wide variety of situations.

The forms are moveable up and down the neck

One of the most powerful aspects of these triad chord shapes is that they are completely moveable up and down the neck. This enables you to play different chords using the same simple shape just by moving to a different fret.

This fact makes these chords perfect for traveling to different locations on the neck. It enables you to play the chord that’s called for while at the same time it gives you several chord voicing options. One voicing of the chord can give you a completely different feel than another because one may use higher notes than another.

Using different inversions also lends a different sound to the same chord.

Finally since you can move these shapes anywhere to reach different chords, knowing just a few simple shapes makes it possible to play a huge variety of chords and voicings.

Their simplicity makes them incredibly versatile

As I’ve mentioned a couple of times, since the chords contain only three notes, they are extremely easy to learn and to play. It’s also quite easy to move from one triad to another because you’re dealing with just three strings.

But there’s more to the versatility these chords offer than just being easy to play.

Major triads provide accent without muddying the mix

Because they contain the smallest number of notes possible for a chord, you can comfortably play them in a huge variety of situations without “muddying” the overall sound.

For instance, if you’re playing with another guitarist or a band, sometimes playing a full five- or six-string chord just creates too much sound. It all begins to sound like a big wall of mush.

Instead, if you use a simple three-note chord, you can carve out a small sonic space that leaves room for another guitarist, a bass, keyboards, and other instruments. Laying back with a simple major triad even opens up the sonic space for the vocalist.

Once you learn these chords, you will never run out of possible uses for them. And it matters little what genre of music you play. These chords fit in as comfortably on a rock song as they do in a country tune or a folk ballad. They work just about anywhere!

Three moveable shapes of major triads

So, now that we know how useful major triads can be, let’s take a look at three triad shapes that I find particularly useful.

You’ve already used major triads if you’ve read

It’s easier than you think to learn how to play a chord on guitar

The good news is that you probably already know these shapes! You may not have looked at them in this light before, but it’s likely you’ve used each of these shapes in your playing already.

You can use many forms to play major triads. Here we’ll concentrate on three shapes that use just the three thinnest strings on the guitar: the G, B, and High E strings.

The E-shape major triads

In the article in the call-out above, I taught you how to play a simple E chord. It consists of the notes E, G#, and B. Those are the three notes of the E major chord.

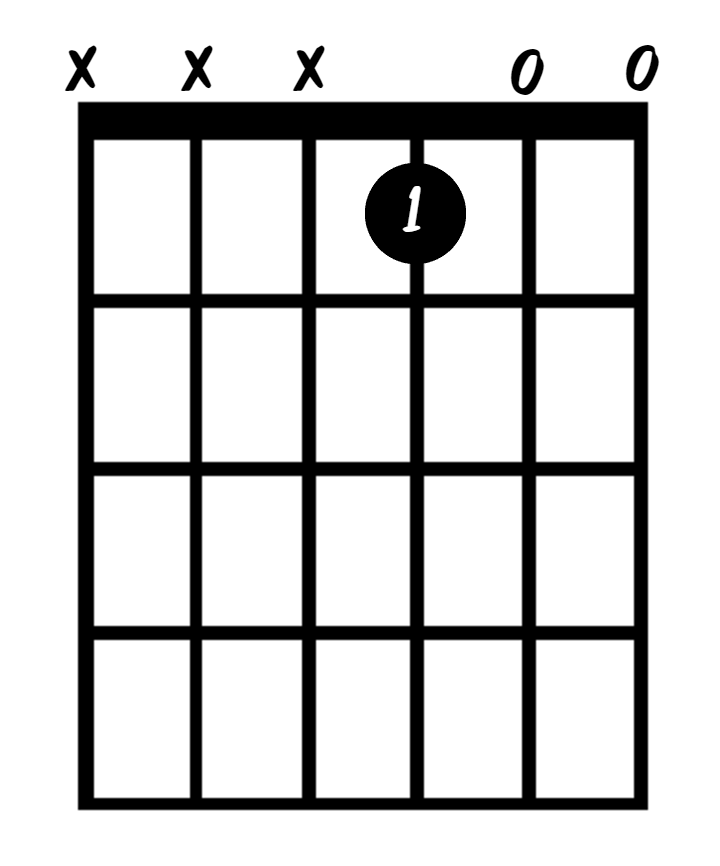

Here’s the chart I showed in that article which shows that in order to play the simple E chord, you need only press the G string at fret 1 to make a G# note. Strum that along with the open B and open E and you have E major.

Notice that this shape uses two open stings. In order to play this chord shape anywhere on the neck, you just need a way to push those two strings down one fret lower than the note on the G string.

To do this, press both strings with your first finger. This is called a bar (or barre) and you accomplish it by laying your finger flat across both strings.

For instance, if you want to play an A chord with this simple shape, lay your first finger across the E and B strings at fret 5 and press the G string down at fret 6 with your middle finger.

This shape yields the first inversion of the major chord. Fret 6 of the G string gives you the note C#, the 3rd note of the A major scale. Fret 5 of the B string gives the note E, the 5th of the scale. And finally, fret 5 of the E string gives the root note, A.

This might be the most comfortable shape of the major triads. First, it’s very easy to play once you master the small two-string bar technique. And second, it’s very easy to know what chord you’re playing because the root note lands on the E string.

Don’t yet have the notes on the E string memorized?

You can move this shape to any fret to play the major chord of the note on the E string at that fret.

The A-shape major triads

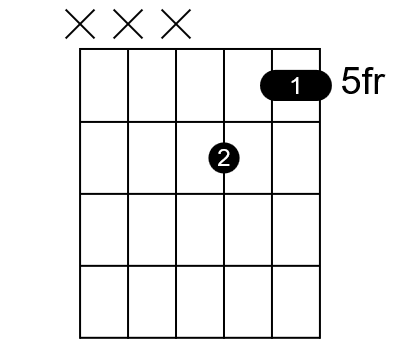

The simple form of the A major chord also serves as one of the moveable major triads. This shape gives you the major triad in the root position since the root note is the lowest note in the chord.

Just like with the E shape above, in order to make this shape moveable, you just need another finger to hold down a note that’s on the open E string in the simple A shape.

To accomplish this use your pointer on the E string. Then use your ring finger on the G string and your pinky on the B string.

While you can play this shape nearly as easily as the E shape above, it’s a little harder to locate this A shape. Still, it’s not that difficult as long as you know the notes on the A string cold. Whatever note sits on the A string at the fret where your first finger is identifies this major chord.

Don’t know the notes on the A string?

So the diagram above shows a D major triad. Why? because the first finger is at fret 5. Fret 5 on the A string plays the note D. So this is a D major triad which you make by playing the A shape at fret 5.

In this case, fret 7 on the G string (held down by your ring finger) is the root note D. Fret 7 on the B string (under your pinky) is the 3rd of the scale, F#. And finger 1 frets an A (the 5th of the scale) at fret 5.

Move this shape up two frets to play an E. Or move it down two frets to play a C. And so on.

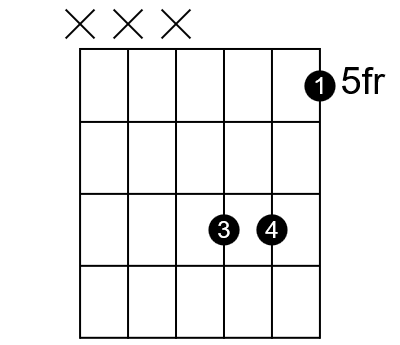

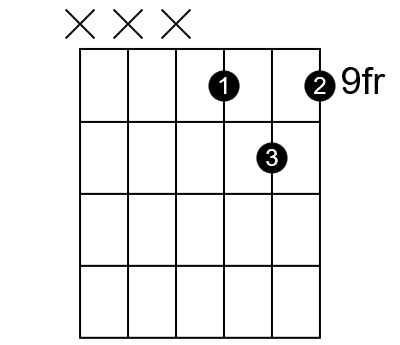

The D-shape major triads

The second-inversion shape of major triads should be easy for you because you already know this shape. If not, read the article on learning how to play chords linked above. This is simply the shape of a basic D major open chord. Just move that shape to another fret to achieve a different chord.

For instance, move the shape up two frets to create an E chord. Move it up to fret 9 to play an A chord.

This is a really fun shape to play, and it sounds great as an alternate chord form or for chord stabs as accents.

Unfortunately, of the three shapes in this article, this one presents the biggest challenge for figuring out where to play it.

For me, it’s most helpful to realize that the root notes sits on the B string. Then, memorize the notes of the B string so that you know what chord you’re playing no mater where you make this shape.

The 5th sits on the G string, and that leaves the 3rd on the E string. Unless you know your fretboard exceptionally well, neither of those provides much help in locating this chord shape. So as I said, I find it best to know the notes on the B string and then identify the chord by the location of the root note under your ring finger.

Major triads don’t stop there

In this article I’ve talked about just three shapes you can use to make major triads. And we limited the discussion to just the three thinnest strings on your guitar.

But many more possibilities exist. you can use any set of three adjacent strings to find major triads. You’ll need different shapes to play them, but they are there.

For times when you need to fill out the bottom end a bit, you can create your triads on the Low E, A, and D strings. Or use the D, G, and B strings for a more middle ground. So many possibilities!

And you can make your own just by combining the 1, 3, and 5 of the scale across three strings. Experiment. You’ll be surprised at what you can come up with.

To really up your triad game, learn about minor triads too!

Conclusion

Major triads can be one of your most powerful and versatile tools as a guitar player. You can use them in countless situations across virtually any genre or style of music. They work as well for rhythm guitar parts as they do for lead guitar parts.

Three simple chord shapes provide the shapes you need to play the root position major triad as well as both inversions. You can move them anywhere up and down the neck to transform them into whatever major chord you want to make.