The minor pentatonic scale might just be the most important scale for guitar players to master. Particularly important for lead guitarists, it provides a versatile and powerful framework for solo improvisations and lead lines. In this article we’ll take a close look at the minor pentatonic scale and how to use it.

What is the minor pentatonic scale?

The minor pentatonic scale is a musical scale which consists of five of the seven notes of the natural minor scale. Specifically the minor pentatonic scale consists of the 1, 3b, 4, 5, and 7b degrees of the natural minor scale. It is arguably the most versatile and valuable scale for lead guitar improvisations and lead lines.

I’ve talked about the pentatonic scale in general and specifically the minor pentatonic scale in different articles on this site. If you haven’t already read my article What is the pentatonic scale: a complete exploration, you might want to go read that first.

Five minor pentatonic scale patterns

Just as with the major pentatonic scale, you can use five different patterns or boxes to play the minor pentatonic scale. In fact, the major and minor pentatonic scales use exactly the same boxes.

Each of the five boxes start on successive degrees of the scale, and thus land in different positions for the minor pentatonic scale then they do for the major.

For instance, Box 5 of the major pentatonic scale and Box 1 of the minor pentatonic scale use the same shape. While this gets a little confusing at first, the key point involves the location of the root note in each box. We’ll point these out for each box later in this article. Do yourself a huge favor, and learn where the root notes sit in each box!

Finding the location of each box

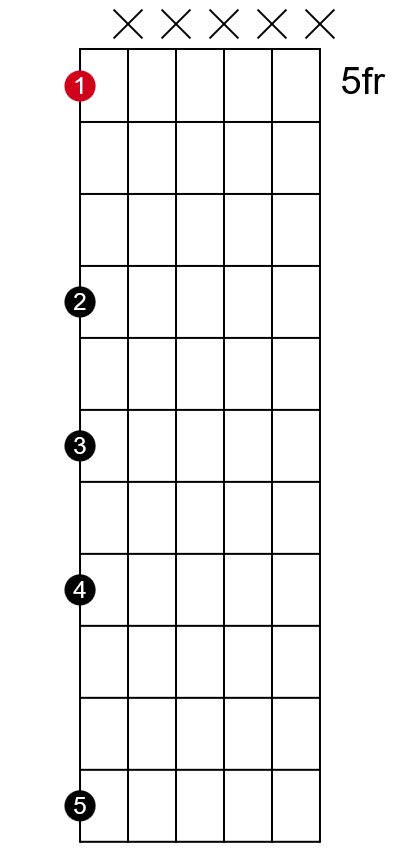

Just as we did with the major pentatonic scale in the article mentioned above, we can lay the minor pentatonic scale out up one string to locate the starting note of each box. We’ll do this in the key of A minor.

First, find the note A at fret 5. That’s the lowest note of Box 1, and it’s the root note of the A minor pentatonic scale.

Now we just move up the string to locate the remaining four degrees of the scale. Remember that we skip the second degree of the natural minor scale. So, three frets up we have the flat third of the natural minor scale. That’s the note C at fret 8. It’s the second degree of the A minor pentatonic scale, and the lowest note of Box 2 of the scale.

Two more frets up, the note D—the third degree of the scale—becomes the lowest note in Box 3 at fret 10.

Two frets up to E at fret 12, which becomes the fourth degree of the minor pentatonic and the lowest note of Box 4.

Finally, three more frets up takes us to G at fret 15, the fifth degree of the A minor pentatonic and the lowest note of Box 5.

And of course, if you have room on your guitar, the whole thing starts over again with the A note at fret 17. You’ll find Box 1 here too.

Now we know where the lowest note of each of the five boxes sits. Thus we know where each box starts.

What are the minor pentatonic scale box shapes?

Now that we know where each of the five boxes start in the key of A minor, let’s take a look at each box. Pay close attention to where the root note sits in each box. That’s critical information when it comes to using the boxes in your solos and lead lines.

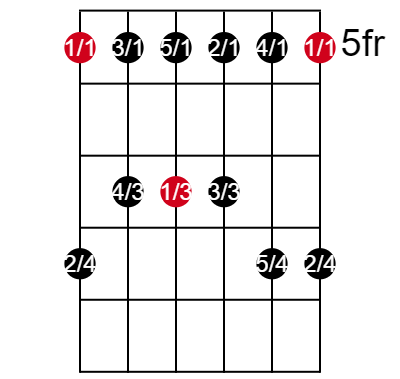

Box 1 of the minor pentatonic scale

The first box of the minor pentatonic scale might just be the most common scale pattern in all of guitar world. Certainly the blues and genres that spawned from it make great use of this box.

Many, if not most, new guitarists learn this box as their first introduction to playing lead guitar. In fact, it’s almost become so cliché that some players don’t want to use it any more. But don’t be like that! It remains a critically important shape from which many of the most iconic riffs ever have been born.

I won’t go through these boxes step by step. Refer back to the complete exploration article for that type of walkthrough. Just remember that I’ll use the same convention in these box charts that I did in that article. Namely, the first number in each circle refers to the scale degree of the note, and the second number identifies the finger I suggest you use to play that note.

Note that this box matches Box 5 of the major pentatonic scale.

Box 2 of the minor pentatonic scale

Box 2 starts with the second degree of the scale as the lowest note. So, in the key of A it starts on the C note at fret 8.

Notice that I suggest using the first and third fingers on the highest two strings. This forces a slight hand shift. You could avoid the shift and instead use fingers 2 and 4.

However, you’ll often want to bend those strings. Using fingers 1 and 3 puts you in a much better position to do that since your ring finger provides more bending power and control than does your pinky.

Note that Box 1 of the major pentatonic scale uses this same pattern.

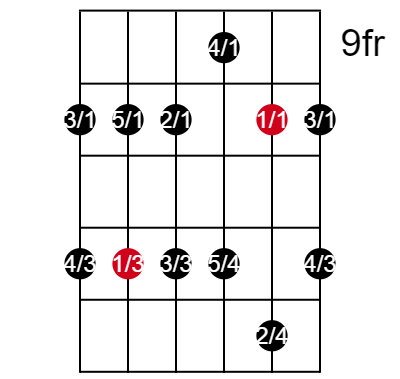

Box 3 of the minor pentatonic scale

This box starts on the third degree of the scale. In the key of A minor, that’s the D at fret 10.

This box seems the hardest for some players to learn and use because of the required hand shift between the G and B strings. But don’t let that stop you from mastering it. It can lead to some great creative licks and riffs.

I also force another hand shift with my suggested fingering on the lowest three strings and the highest string. Again, this fingering puts you in a stronger, more controlled position for bending. You could also use the fingers 2 and 4 fingering if you prefer.

Note that the major pentatonic scale uses this same pattern for Box 2.

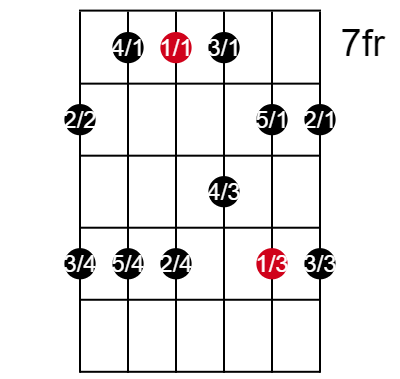

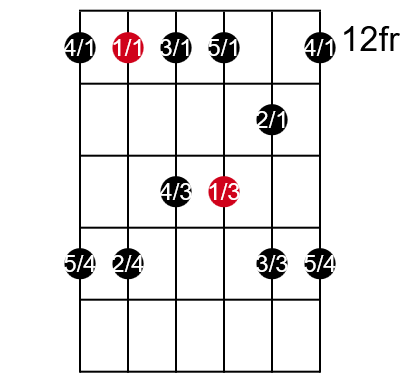

Box 4 of the minor pentatonic scale

Box 4 had traditionally been the second of the two boxes I used for years before I mastered the other boxes. I think that’s because it’s easy to play since it’s similar to Box 1. Also, in the key of A minor it’s easy to find since it sits comfortably with the E note at fret 12.

Here I’ve shown the two notes on the B string as played with fingers 1 and 3. Honestly though, I think I probably use 2 and 4 just as often. Maybe more often.

For me personally it’s a tossup. the 1 and 3 fingers provide more strength and control. But the 2 and 4 fingers allow for faster playing since that fingering doesn’t force a hand shift.

Pick your favorite. Like me, you might find that which fingering you use often just depends upon the situation and the riff you’re playing.

If you’re on an acoustic guitar, you’re likely going to find it hard to play this pattern unless your guitar has a cutout. Remember, you can drop down an octave and play this pattern at fret 0.

Note that Box 3 of the major pentatonic scale uses this pattern.

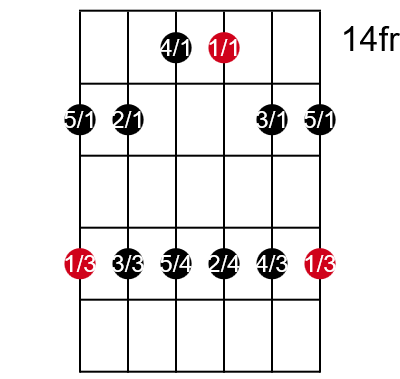

Box 5 of the minor pentatonic scale

Box 5 is another that’s easy to learn since most of the notes fall perfectly into line on two frets. But some players find it challenging to use.

You might be tempted to use fingers 2 and 4 on the bottom two and top two strings, but I like to shift my hand position slightly to use my pointer and ring fingers.

Just as I suggested earlier, these two fingers provide more strength and control, particularly when you bend notes. Because I suggest you use this fingering, I’ve used that in the chart here.

Also, you might find it just as easy to stretch up with the third finger on the G and B strings instead of switching to finger 4. Especially high up on the neck where the fret distance is much smaller.

In general, I’m opposed to this type of stretch because I think you benefit greatly by being capable of using your pinky whenever a long stretch is required. Not everyone agrees with me, and some very accomplished players rarely, if ever, use their pinky.

I just think it’s a mistake. You have it. Use it. That way when you get into a situation where you really need it, you’ll be used to commanding it to do what you want.

If you’re on an acoustic guitar, you’re likely going to find it very hard–if not impossible–to play this pattern even if your guitar has a cutout. Remember, you can drop down an octave and play this pattern at fret 3.

Note that Box 4 of the major pentatonic scale uses this same pattern.

Why is the minor pentatonic scale so important?

You’ve likely heard the minor pentatonic scale in hundreds of songs and guitar solos. Especially in classic genres of blues and rock and roll.

One could argue that it’s the most important scale for lead guitarists. Even more important than the major pentatonic scale. But why? What makes this scale so important and useful?

The minor pentatonic is easy to learn and play

The pattern for Box 1 of the minor pentatonic is really the easiest of all the boxes–major or minor–to learn and use.

Because the root note lands under the first finger on the first fret of the box and the lowest string of the guitar, psychology seems to be at play. It’s simply just the most comfortable shape in the most comfortable position. Thus new players can easily grasp it and remember it.

It’s easy to run up and down the scale, and you can quickly pick up quite a bit of speed as you blow through this box.

Box 1 reigns as king of all lead guitar patterns.

So, this pattern gives new players confidence. You can get comfortable with it very quickly. And you can start using it to improvise your own lead solos virtually on day one of learning it.

Thus Box 1, and by definition the minor pentatonic scale, are responsible for more players becoming lead guitarists than any other. It’s where pretty much everyone starts, regardless of what scale becomes their go-to scale later.

You can use the minor pentatonic scale over songs in both minor and major keys

Of course the minor pentatonic scale works great over virtually any minor-key chord progression. But an interesting quirk of history and listening expectations make the scale just as useful over many major key chord progressions too.

Because early American blues players often used the minor pentatonic scale over major-key blues progressions, we’ve been hearing this combination for at least 100 years of popular music.

And the tradition certainly stretches back further than that.

The clash of the major key’s major third degree and the minor pentatonic scale’s minor third causes discomfort.

But when the blues players pass through that clashing moment on their way to other notes, it sounds…well…bluesy. It shouldn’t work, but it does.

And we’re all used to it. Especially since all of the genres that sprang from the blues–including pretty much all pop music of today–often use the same device. We’re completely used to it. And we like it.

So, the minor pentatonic scale is extremely versatile.

Why does the minor pentatonic scale work so well for improvisation and solos?

As I discussed in the articled linked at the top of this post, the pentatonic scales are formed by eliminating the notes that cause the two half steps in the parent major and minor scales. Essentially, this removes the tension from the scales and results in a scale whose notes are all comfortable over the most important chords in the key.

Magic for 12-bar blues

This holds especially true for the I, IV, and V chords of a key. This goes a long way toward explaining why blues players found the minor pentatonic scale so comfortable even with their major-key songs.

Since blues songs rely predominantly on those three chords–sometime straight major chords and other times dominant 7th chords–it was pretty much impossible to play a note from the minor pentatonic scale that didn’t work with whichever chord the progression passed through.

Need help with musical terms like dominant 7th, I-IV-V chords, chord progressions, and others?

To be clear, some notes sound better than others with the different chords, but each of the five notes sound reasonably acceptable over any chord in a standard 12-bar blues song.

The minor pentatonic scale provides quick wins

The scale also works so well because once you master the five box shapes we’ve talked about here, improvisation becomes easy. Even beginner players can start having some success with improvisation relatively quickly.

That’s not so say that you’ll be knocking anyone out with your solos after one week’s experience. You still need to master your timing, your groove, your speed, your phrasing, and much more. Still, you’ll be surprised how quickly you can start playing improvisations that actually seem to work.

Also, as I said above, although all five notes can work with pretty much any chord of the progression, some of the notes sound better than others. As you gain experience with improvising with the different boxes, you’ll develop a feel for which notes sound the best over which chords. That’s when the magic really starts to happen.

How to get started with the minor pentatonic scale

OK; by now you’re probably excited to get started creating your own improvisations with the minor pentatonic scale. But how do you start?

First things first: learn the boxes

You have to lean the boxes that I’ve introduced here. Without them, the minor pentatonic scale makes no sense. I suggest you start with Box 1 since that’s the easiest to learn.

Play the box from the bottom to the top and back down again. Play it over and over and over until you really know it. Make sure that at a minimum you understand where the root notes in the box sit. That’s home base and you’ll always feel good coming back to it. So know where it is!

Once you’ve mastered Box 1, do the same with the remaining boxes. It would be great if you can master all five boxes immediately, but that takes some time. And you might be better off for now just learning Box 1 and moving to the next step for a quick win. Just remember to come back and do the same with Box 2!

Play the minor pentatonic scale to a backing track

Nothing helps you learn to paly faster than playing along with someone else. But that’s intimidating, and you might have trouble finding someone with the patience to play along while you learn.

To solve that problem, play along to recorded music. It can be difficult to play along with fully developed recordings of artists, but you can play to backing tracks. These tracks generally provide instrumental chord progressions that you can play along to.

To find many quality backing tracks that you can play along to for free, head over to the Guitar Backing Tracks website. You can also search for the term “guitar backing tracks” for other options.

For a good place to start, type 12 bar blues into the search box. This will bring up a list of backing tracks. Follow one of the links and start the track playing.

As the backing track plays, just run the minor pentatonic scale up and down to get the feel for playing at tempo and to get a sense of how the scale works with the track. Keep doing this until you feel comfortable.

Invent your own improvisational riffs

Now you’re ready to start improvising. Don’t expect miracles from yourself just yet. But just start combining the notes of the minor pentatonic scale in different ways.

Just make up your own riffs. After all, that’s all improvisation is! You might not like everything you play, but it will all teach you something. The more you do it, the more adept you’ll become at doing it.

Now you’re on your way! Don’t forget to do this with the other boxes too.

Conclusion

The minor pentatonic scale is the star of musical improvisation. It’s versatile and easy to play. Plus you can use it over any chord progression in a minor key and many in a major key.

Five boxes exist across the fretboard for the minor pentatonic scale. Once you learn these patterns, and particularly when you understand the location of the root note in each, you hold five powerful improvisational tools in your hand.

After you’ve learned the patterns, you can quickly start to create your own improvisations. Play along to a backing track to get the real feel for playing the music.