In our discussion of the major scale (Understanding the major scale is foundational music theory) we left out the very important topics of scale degrees and musical intervals. If you haven’t read that article, now’s a great time to go do so. You won’t understand much of what we talk about here without the knowledge you gain over there.

While scale degrees and musical intervals are related concepts, they’re not the same thing. Both concepts are extremely important. A basic knowledge of these concepts (and we’re going to keep it very basic!) will unlock the mystery of chord construction, song chord progressions, and more.

They’ll also provide you with valuable language that you will use to communicate with and understand other musicians as you start collaborating and playing with others.

Don’t try to understand scale degrees and musical intervals without a good understanding of the major scale:

So what do these terms mean? The concepts are really quite simple in basic terms, but again, they are really important. And, they can get complex very quickly (especially a discussion of musical intervals), but let’s keep it basic for now. Even that basic understanding takes you a long way.

Musical intervals

We’ve already discussed musical intervals to some extent. We just didn’t call them by that name.

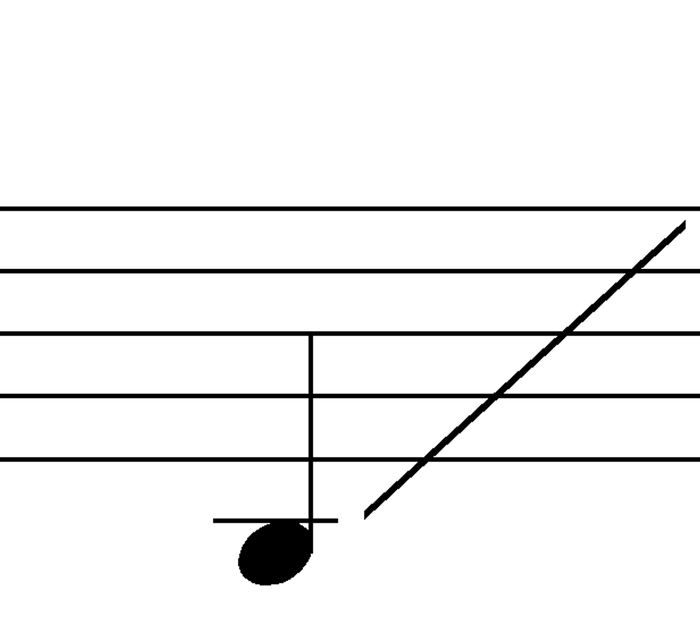

Remember that in the major scale we see this pattern that defines the scale:

W-W-H-W-W-W-H.

Regardless of the note you start on, when you apply that pattern to moving up the chromatic scale, you create a major scale.

This pattern includes whole steps and half steps (thus the Ws and Hs). These steps also have alternate names where Whole Steps are tones and Half Steps are semitones.

The concept of musical intervals categorizes these steps with other names. Before we go much further, we have to introduce another concept: diatonic tones.

Diatonic and chromatic tones

Recall that the major scale represents just one of many scales built from the chromatic scale. It happens to be the most important scale to western music, but many other possible scales also exist.

The major scale uses seven notes of the chromatic scale. In other words, seven of the 12 notes available in each octave. We call these seven notes diatonic notes or diatonic tones of the major scale. That just means they belong to the scale. We call any note outside of the scale a chromatic note.

Musical intervals and scale degrees

Now that we understand that, let’s turn back to musical intervals and scale degrees. What is a music interval?

In music, we call the distance between two tones a musical interval. Intervals can be defined in terms of semitones and tones. For example, the distance between the note C and the note C# is a musical interval of one semitone. The distance between C and D is a full tone. Each major key has 56 different intervals.

But the musical intervals between the diatonic notes (the notes in the scale) are special. So special, in fact that we identify them with a numbering system. Enter scale degrees.

Since the key of C major is the easiest to understand due to the lack of any sharps or flats, let’s use that key and scale for our discussion. Just remembrer that this discussion applies to any key exactly the same way.

The note C, as you might expect, has a special place in the key of C. It’s the note that defines the scale, and can be known by a couple of different names. The technical name is the tonic. While you’ll hear that term often–so it pays to be familiar with it–most often we use the term root note of the scale. The C major scale has a root note, or simply the root: the C note.

Similarly, the G major scale has a G note for the root, the D# major scale has a D# root, and so on.

Naming the scale degrees

What are scale degrees?

Each note in a scale has a particular position in that scale. We identify these positions with a number. In the case of the major scale, we use the numbers 1 through 7, but other scales have more or fewer notes and thus numbers. We can refer to each of these numbers as a scale degree. The first note in the scale has the scale degree 1. The second note has the scale degree 2. And so one for all notes of the scale.

In terms of scale degrees, the root note has yet another name, and that is the one. So the note C is the one of the C major scale. More commonly, you’ll see it written numerically as 1, or perhaps in Roman numerals as I.

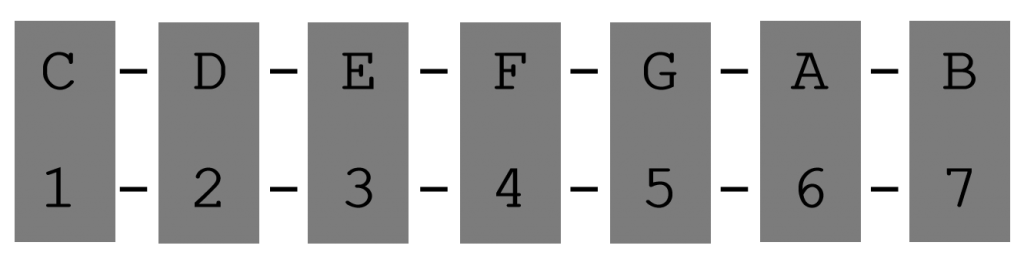

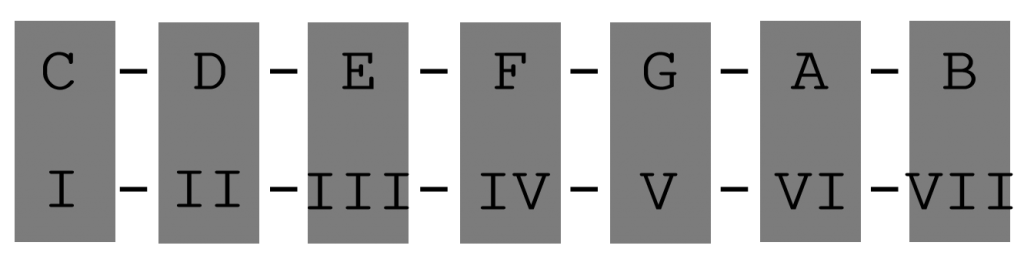

The remaining diatonic notes of the octave–the remaining notes of the scale–are then numbered accordingly. So the note D is the two (2), E is the three (3), and so on up to B which is the seven (7). So, you can number the C major scale with its scale degrees like so:

Or in Roman numerals as:

Naming musical intervals

From this information, we can form a basic, but useful, concept of musical intervals. In the major scale, we call the distance between the first and the second scale degrees a second (2nd). In other words, an interval of a 2nd. More precisely, a major 2nd, but for now we’ll call it simply a 2nd.

We call the interval from the first to the third scale degrees of the major scale a 3rd (a major 3rd to be precise). From the first to the fifth, a 5th (a perfect 5th to be exact).

Using knowledge of musical intervals and scale degrees to communicate

Understanding this can be important when you’re playing with other musicians. If your partner plays a melody and that melody hits a C note, he might ask you to play a 3rd to add some harmony. Now you know the 3rd of C (in the C major scale) as E (look back at the chart above if you need to). So your partner wants you to play an E.

If your partner plays an E note and asks for a 3rd rd above that, you can figure it out looking at the scale degrees listed above. Consider the E temporarily as the 1. The 3rd above E in the C major scale is G, so play a G note to play harmony of a 3rd over E. That same G note is also the 5th of the root note C.

Numbering the scale degrees

While the concept of musical intervals is important, in my opinion it’s even more helpful to understand the concept of scale degrees, so let’s go over it again. A note’s scale degree simply matches its position in the scale.

The root note, as we already discussed, is the 1. It holds place number one in the scale. In C major, that’s the note C.

In C major, the note D holds place number 2, so it’s the 2. E the 3, and so on. Maybe this seems simplistic, and you’re wondering why I’m saying it again. I’m saying it again because the concept of scale degrees is so incredibly useful to understand and master. The charts above list the scale degrees in the key of C major.

Remember; every scale has its scale degrees, but potentially a different number of degrees. For example, the pentatonic scale has only five notes, and thus five scale degrees. Read more about that in my What is the pentatonic scale: a complete exploration article.

Building chords from scale degrees

With the knowledge of scale degrees you can build virtually any chord imaginable. Every chord has a recipe. In the article It’s Easier Than You Think to Learn How to Play a Cord on Guitar we talked about the recipe for making a C chord: combining the notes C, E, and G makes a C chord. But we didn’t talk about why this is so.

Look back at the scale degrees of the C major scale. You’ll notice that the C is the 1, the E he 3, and the G the 5. From this we can extrapolate and see that the recipe for any major chord is the 1, 3, and 5 scale degrees played simultaneously.

Any time you play the 1, the 3, and the 5 of any major scale, you are playing the root chord of that scale.

And in fact, if you pick any note and temporarily consider that the 1, you can add the 3 and 5 of that note’s major scale to form a major chord.

That last sentence sounds confusing even as I write it, so let’s take a couple of examples.

Build a G major chord

Say you’re in the key of C and you want to play a G major chord, but you don’t necessarily know which notes to combine to make the chord. First, make a temporary mental shift to the G major scale (since you want to make a G chord). The G major scale includes the notes:

G-A-B-C-D-E-F#

Now use your knowledge of scale degrees to find the other notes you need for the chord.

G is the 1. You know you need the 3 and the 5 to complete the major chord. You also know (or can figure out with the major scale recipe) that the third note in the G scale is B and the fifth note D. So, to make a G major chord, play G, B, and D at the same time.

Build an E major chord

Do the same to find an E major chord. The notes of the E major scale are:

E-F#-G#-A-B-C#-D#

You can easily see that E is the 1, G# the 3, and B the 5. Play those three notes together and you have an E major.

And this system works for every major chord. Just construct the major scale based off of the root note that represents the chord you’re trying to build and use your knowledge of scale degrees to identify the notes you need to add in order to make the major chord.

An interesting side observation

If you look back at the recipes for the G and E chords we just figured out, you might notice something interesting.

Notice that the three notes (or scale tones) that make up the G chord also exist in the C major scale. However, the E chord has one note that is not common to the C major scale: the G#.

What does that tell us? We’ll talk more about chords in other articles, so I won’t get too deep here, but essentially this shows us that the G major chord will fit comfortably into a song in the key of C major. Why? because the three notes that make a G chord–G, B, and D–are all notes in the C major scale.

Likewise, a C major chord will fit comfortably into a song in the key of G major. A C major chord uses the notes C, E, and G. All three of these notes are found in the G major scale.

The E chord, on the other hand, might not fit comfortably into a song in the key of C major. An E major chord uses the notes E, G#, and B. That G# does not belong to the C major scale, so the E major chord could feel somewhat out of place with C major.

Uncomfortable doesn’t mean “wrong”

Notice that I said “comfortably” above. One important thing about music theory rules: like other rules, sometimes it pays to break them. And breaking the rules of music theory can often result in some of the most interesting and creative music around.

Even though the chord E major doesn’t “belong” in the key of C major, writers can do whatever they want, so you will indeed find E chords in some C major-based songs. Including an out-of-scale chord can add some real unexpected interest to the song. Just the same as using a chromatic note (a note off of the scale you’re using) will add an interesting spice to a melody. We’ll talk about concepts like these in future articles.

Scale degrees are not just helpful with simple major chords

Major chords, as we’ve discussed here, are among the easiest chords to build, but you can build all other chords–even the most fancy, finger-twisting guitar chords–with this same basic knowledge of musical intervals and scale degrees. We’ll save more complicated discussions for future articles, but you now have a good basis for understanding chord construction.

Why stuff this musical interval and scale degrees junk into your head?

I know; you already have enough to think about and remember. So, do you really need to know this stuff to play the guitar? No, honestly you don’t. You could just use rote memorization skills to remember how to play a G major, a C major, and any other chord. Or, you could just use chord charts to see where to put your fingers to make the necessary chords.

But I am convinced that knowing how these things are put together will make you a better guitar player faster. It’s somewhat natural to initially feel like these technical rules just junk up your head. But in truth, understanding issues such as scale degrees and musical intervals can make you not just a better guitarist, but a more creative guitarist too.

Knowing these concepts gives you freedom to strike off into wild new creative territory while maintaining some sense of where you are and where you’re going.

It’s like going on a hike through the wild. You don’t have to know east from west, and you don’t have to bring or know how to use a compass. You can go hiking without any of that “junk” in your head.

But wandering too far from the known trail without that knowledge could end up with you being hopelessly lost, so you’re going to be inclined to stick to the trail you know. It’s the difference between going on an adventure and going for a walk.

In the same way, you have to ask yourself if you’re content sticking to the musical trail you know, or if you’d like the knowledge and the tools that give you the confidence to take some musical adventures into territory you’ve never ventured into before.

Conclusion

As you’ve seen, musical intervals and scale degrees are related, yet not quite the same.

These concepts give you common language you can use to communicate with other musicians. They help make musical collaboration easier.

But they do so much more than that. They give you the tools to understand chord construction. You can use the knowledge to build anything from a simple major triad chord (a major chord with just three notes) to the most sophisticated jazz chord you can imagine.

We’ll talk more about scale degrees and musical intervals in other articles. Here we’ve only scratched the surface of using these concepts to construct chords.

And we haven’t even touched on the ideas of chord progressions yet. But you’re now also poised for those types of discussions with your knowledge of scale degrees and musical intervals.

6 comments