Simply stated, you can’t play the blues without the dominant 7th chord. Oh, and you can’t play jazz. Rock and roll. Country, folk, gospel and worship. You name it. If you’re going to play it properly, then you need the dominant 7th chord. So let’s take a good look at the dominant 7th chord so you understand it and, more importantly, know how to use it.

What is a dominant 7th chord?

A dominant 7th chord is a collection of musical notes that includes the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and the flatted 7th degrees of the major scale. In a chord chart, the chord is denoted by the name of the chord followed by the number 7. For instance, a C dominant 7th chord is written in chord charts simply as C7. Any major chord can be transformed into a dominant 7th chord. To turn a major chord into a dominant 7th chord, add the flatted 7th note to the chord.

Need to learn how to make a major chord?

Dominant 7th chords are critical to many genres. The blues relies on these chords particularly extensively. Thus we’ve come to hear these chords as one of the signature sounds of the blues. And any style that evolved out of the blues naturally also relies heavily on the dominant 7th sound.

What is the function of a dominant 7th chord?

Dominant 7th chords sound cool. That’s as good of a reason to use them as any! But they do serve some very specific purposes that help you tell a musical story. They help you lead your listener on a comfortable journey. And they give you a bit of power over your audience’s emotions. Let’s take a look at a few specific things these chords can do for your compositions and performances.

They make the V chord more interesting

Perhaps the most common use for the dominant 7th chord relates to the 5th scale degree of any key. In any key, you can substitute the dominant 7th for a straight major chord at the 5th degree. Written more musically, you can substitute V7 for V.

And it nearly always sounds fantastic. In fact, it’s likely more common to play the V7 instead of the V in most popular genres of the past 100 years or more.

For example, in the key of E, you have E major as your root chord and B as your V chord. Playing a B major sounds kind of bland. But toss in a B7 instead and you have absolute magic. That’s magic that’s been used thousands upon thousands of times. And it never loses its magical sound.

Don’t know how to make an E chord?

Learn open chords to play thousands of guitar songs

What about a B chord?

That one extra note added to the major chord–the flatted 7–makes the chord sound indescribably more interesting. And this makes the V7 more interesting than the straight V.

But not only does it make things more interesting, it makes the music more powerful. It’s far more compelling to hear that dominant 7th on the V chord than the V alone.

And what more proof do we need than the blues? Most blues songs contain exactly three chords. The I, the IV, and the V. But it’s rarely the V. Far more often—in the blues, maybe always it’s the V7. People have been listening to that for over 100 years and still the blues thrive.

Add interest to a chord progression through instability

So what makes the dominant 7th chord so powerful? It’s a matter of instability. The dominant 7th chord acts as a dichotomy that provides comfort and guidance in its inherent instability.

The dominant 7th chord is quite unstable. By this I mean that it’s not a chord that feels very comfortable on its own. It’s not a great place to stop. It wants to “go” somewhere. In musical jargon, it wants to resolve to another chord.

In the case of the V chord, when you play a straight V in a progression, it’s pretty comfortable. It’s a very stable chord, so you don’t feel so compelled to move off of it. And this means you’re listener doesn’t necessarily feel much of an urge to see where your music goes next. This is the bland feeling I talked about that you get from the V as a straight major chord.

The dominant 7th in the V position can save you from this boring path. The V7 builds up a situation of tension and release. Because the dominant 7th chord contains instability and a bit of discomfort, you don’t want to stay there. Instead, you’re compelled to find a chord to go to that relieves the tension of the dominant 7th.

Lead the listener back to the root chord

So, where does that dominant 7th want to take you? When you play the V7 in a progression, the chord that resolves that tension the most effectively is the I. The root chord. Going from the V7 into the I creates the feeling of coming home to rest.

When the listener hears the V7, they don’t realize it, but they long to hear the I as the next chord. And when you give it to them, it pleases them and they like your song maybe just a bit more than they otherwise would have. Maybe a lot more.

In our example with the key of E, the B chord feels boring. It leaves the listener disinterested. They don’t really care much what happens next and you can easily lose their attention.

But replace that B with a B7, and now you’ve perked their ears up. That B7 sounds interesting. It’s uncomfortable. It wants to resolve so a comfortable place. And the listener wants the tension of the B7 released.

That’s when you give them the I chord. The move from V7 to I is familiar and comfortable. By now it’s even expected.

That’s not to say that there’s never a place for the straight major V. Maybe the V7 has become so familiar that a straight V actually gets more attention once in a while. But it’s once in a while. A great while. Do it too much and you will bore your audience.

How to play a dominant 7th chord

So how do you construct dominant 7th chords? Recall that earlier I pointed out that to make one, you add the flatted 7th scale degree to the major chord. It’s really quite simple to turn most any major chord into a dominant 7th. Let’s learn dominant 7th shapes for the seven natural major chords.

Remember, in all cases you need the I, III, V, and bVII degrees of the scale to make the dominant 7th chords. Well…almost all cases as you’ll see.

How to play A7

The notes of the A major scale are:

A, B, C#, D, E, F#, G#

To play A7, you start with the notes A (the root), C# (the 3rd), and E (the 5th) to form the major chord. You also need the flatted 7th. Look at the notes in the scale listed above to easily see that G# holds the 7th scale position. When you flat G# you end up with G.

So, to turn an A into an A7, add the note G.

When you’re playing A in the open position, you have two options for adding that G note. First, you can lift your pointer and let the G string ring open. This results in what I call sort of a “soft” or more subtle A7. Because that low G note doesn’t stand out very strongly, it gives the chord a little bit of a more gentle dominant 7th sound.

The other way to make A7 brings your pinky into the action, and it results in a much more “in your face” dominant 7th sound.

Start with the open A shape and leave all of your fingers where they are. Now add your pinky at fret 3 of the High E string. This adds the necessary G and because it’s the highest note of the chord, it really cuts through. It provides a very powerful sense of the dominant 7. I prefer this form most of the time. Still, the other form has its times and places, and I use that too.

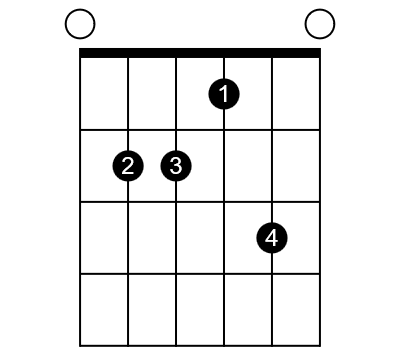

How to play B7

The notes of the B major scale are:

B, C#, D#, E, F#, G#, A#

To play B7, you need the notes B, D#, and F# to form the major chord. Now flat the 7th from A# to an A and you have your dominant 7th.

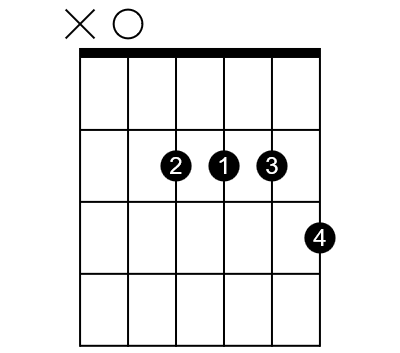

While the chord B doesn’t have a handy open position, the chord B7 does. And this shape becomes especially useful and powerful when you’re playing the chords of E major in the open positions. You now have comfortable open positions for the I, IV, and V7 chords of the key of E. And those are arguably the most important chords of any key.

To play the open B7 requires a bit of dexterity. It’s another chord that’s a bit of a finger twister at first. And it requires all four of your fretting fingers, so it feels kind of complicated.

But once you get used to it, it’s easy. And you’ll use it so often that it will soon become completely natural for you.

First, press the B note at fret 2 of the A string with your middle finger. Next, with your pointer, press fret 1 of the D string for your D#. Your ring finger at fret 2 of the G string plays the A note—that’s your flatted 7th. And finally your pinky plays the F# at fret 2 of the high E string.

Don’t play the Low E string, and be very careful not to touch the B string with your ring finger or pinky. Let it ring open for another B note to add even more character to this chord.

So, as I said, it’s a challenge at first. But stick with it. This is a critically important chord for guitarists and you really have to know it!

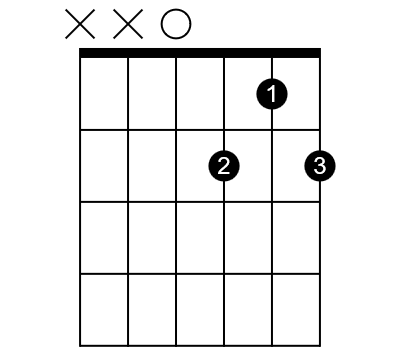

How to play C7

The C7 shape is nearly as comfortable and easy as the open C shape that you’ll use so often in country and folk songs.

The notes of the C major scale are:

C, D, E, F, G, A, B

Use the open C shape to play the C, E, and G notes. Then with your pinky, press fret 3 of the G string for the note Bb. Bb is the flatted 7th note that makes this a dominant 7th chord.

Notice something interesting about the C7. When you put your pinky down on the G string, you do indeed add that Bb you need. But you also eliminate the G note that you need in a major chord. So how can this be a C7?

Technically, I guess you might call this a C7 (omit 5), but no one does that.

The guitar only has six strings (usually). And you only have so many fingers. There is a G note at fret 3 of the E strings, but you don’t have fingers to comfortably play either of them. So, for the C7, we just leave the G out.

Without getting too sidetracked in theory here, we can get away with leaving the V out because it’s the least important note of the chord. In fact, the V note adds little more than seasoning to the chord.

Without the root note, you wouldn’t know what chord you’re playing. If you left the III out you wouldn’t know if the chord was major or minor. And with no bVII you wouldn’t have a dominant 7th chord. But nobody misses the V. You can easily leave it out and everyone will know exactly what chord you’re playing (or at least they’ll feel it).

How to play D7

The notes in the D major scale are:

D, E, F#, G, A, B, C#

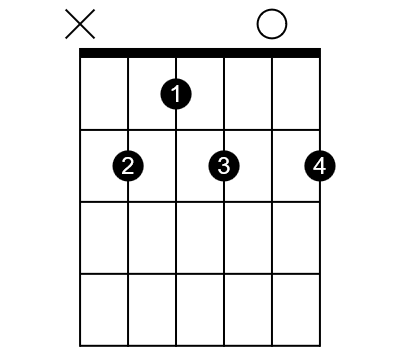

So the notes of the D7 chord are D, F#, A, and C.

This chord is very similar to the open D, but it requires a little shifting of finger position.

Start with your pointer on fret 1 of the B string for the C note–that’s the flatted 7th. Press fret 2 of the G string with your middle finger for the A. And finally, fret 2 of the High E string with your ring finger for the F#. Play the open D string for your root note.

How to play E7

The notes of the E scale are:

E, F#, G#, A, B, C#, D#

To play E7 you need E, G#, B, and D.

Similar to the A7, you have two main options from the open E position to turn E into E7. First, for the more subtle E7, lift your middle finger from the D string to let it ring open for your flatted 7th note.

Or, for a more powerful E7, leave the open E string fully fretted and add the D note at fret 3 of the B string with your pinky.

And there’s no reason why you couldn’t combine these two techniques. Lift the middle finger for the open D and place the pinky for that high D. Now you have two flatted 7ths. For that matter, you could have done the same with the A7 above.

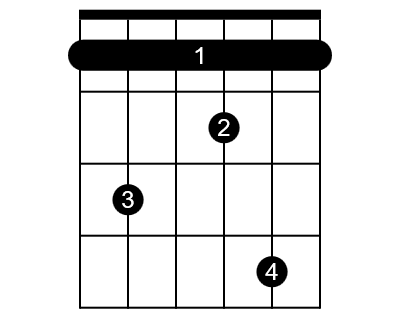

How to play F7

The notes of the F major scale are

F, G, A, Bb, C, D, E

To make F7, you could use the bar chord form of F major and use the same techniques you just learned for turning E into E7. Just make sure you move to a bar at the first fret. And here you do end up with the combination form I talked about with the E where you have to flatted 7th notes.

You can simplify the shape a bit, although I find it almost more difficult to play than the full bar, so I rarely use it. To play it, bar fret 1 on the top four strings with your pointer. Then play fret 2 of the G string for the note A with your middle finger. Play just the top four strings.

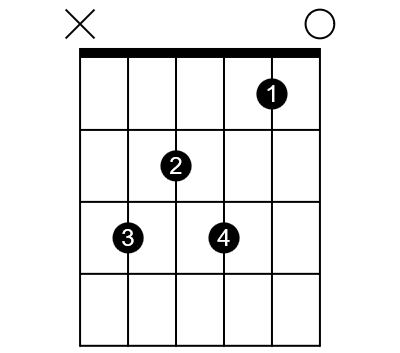

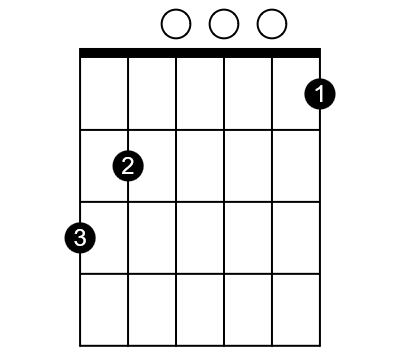

How to play G7

Finally, the G7. This is another super easy chord to play. Especially if you use my recommended fingering for the open G chord you can transform open G to an open G7 with virtually no effort.

The notes of G major are:

G, A, B, C, D, E, F#

So, to make G7 you need G, B, D, and F.

Start with the open G chord. Now, lift the pinky off of the High E string and instead, press fret 1 of the High E with your pointer. This replaces the G note with the F note you need.

Don’t worry about removing that G root note. Remember, you have two other G notes in this wide-open chord. One at fret 3 of the Low E and the other at the open G string. This is a very comfortable and easy-to-reach chord.

What makes the dominant 7th chord so powerful?

One last word about the special characteristic of the dominant 7th chord that gives it such power. Remember that I said dominant 7ths are unstable and a bit uncomfortable. And it’s this very instability that makes them so interesting. But what makes the chord unstable?

I’ve repeated several times that it’s the flat 7th degree of the scale that makes the chord a dominant 7th. And it’s that flat 7th degree that makes the chord unstable. Hopefully you’ve made the connection that the flat 7th is not actually a part of the major scale. In fact, it’s “borrowed” from the minor scale.

So this chord mixes the major and minor scales. That causes confusion. Suddenly the mind hears something that doesn’t “belong”. Something’s just a bit out of whack. That causes discomfort. It also causes a bit of the blues.

Learn how to use dominant 7th chords in a 12 bar blues progression

But it’s a beautiful discomfort and one that we’ve grown quite accustomed to hearing. So we’re comfortable enough with the sound that we don’t hold our ears cringing at the dissonance.

Maybe somewhere back in the 15 or 16 hundreds, audiences laughed if someone hit a dominant 7th, but starting around then it spread through pretty much all of western music. And the early blues players took it and made it their own.

Now we wouldn’t know what to do without it. But the roots of instability remain embedded in the chord so that despite our familiarity and acceptance of it, it still serves its critical purpose of adding wonderful touches of tension to our chord progressions.

And it’s here to stay. For a while at least.

Conclusion

The dominant 7th chord has earned an important place in virtually all modern western musical genres.

To create the chord, the musician adds the flatted 7th degree of the major scale to the major chord. This adds tension into a chord progression. It’s most common to replace a major V chord with a V7 chord—the dominant 7th.

The blues has adopted the dominant 7th into a special place of prominence. Jazz also make extensive use of the chord. And all of the genres that have sprung from the blues inherited the use.

Most of the natural chords have comfortable and easy open shapes for the dominant 7th.

The power of the dominant 7th lies in its inherent instability. Chord progressions don’t land comfortably on a dominant 7th, and they want a strong resolution to a more stable chord. Typically these resolve very nicely to the root chord.

Dominant 7th chords will be critical to most any style of guitar playing, so they are critical to learn.

Thank you so much,my eyes have been open .

I’m glad to hear that, William! Thanks for reading and taking the time to comment. Good luck on your journey!